The question first hit me on a summer morning when I was six (yes I remember this so well !). I remember waking up in our very first house—the one that still holds all the good memories—and wandering into the bathroom. I saw myself in the mirror and just… stopped. It wasn’t about liking or disliking what I saw; it was a sudden, overwhelming sense of sheer randomness.

Why me? Why this specific face staring back? What were the odds I wasn’t born in another country, with entirely different DNA, looking nothing like this? What if I had different parents, went to a different school, and knew a completely different set of people? Why this particular life, right now? We didn’t have a computer or internet back then, so my childish curiosity went unanswered. But honestly, I don’t think a search engine would have helped. This question became a quiet torment for years. The more I wrestled with “Why me?”, the more a deeper, more fundamental question surfaced, teaming up with the first to battle my mind. My parents, bless them, would tell me to stop thinking about questions that even philosophers couldn’t answer. That second question was, of course: “Who am I?”

If I didn’t know who I was in the first place, how could I possibly understand why I was? I couldn’t answer either, so eventually, I let it go and focused more on watching cartoons and studying. But here I am, 18 years later. I still don’t have the answer, but I’m no longer letting the question go. Instead, I’m writing down everything I’ve searched for, discovered, and read. I’ve come to believe that you can’t truly be successful or do great things without a clear sense of who you are—your limits, your strengths, what you love, and what you can’t stand. No one can know themselves 100%, of course. The journey of self-discovery is about chipping away at the iceberg, understanding what we can, and being okay with the vast, hidden parts that our subconscious holds onto.

In a way, this post is for me more than anyone. It’s an attempt to take a universe of messy thoughts and lay them out, to find some clarity in the chaos. We’ll start with some core philosophical and psychological concepts, play with a few thought experiments, explore diverse perspectives from history’s great thinkers, pull some insights from modern psychology, and end with some practical, reflective angles to help you on your own journey. Let’s begin.

One of the things I love most about philosophy is that a single question can have a dozen different answers. They can be contradictory, complementary, or just plain strange, but they are almost always well-argued. This is certainly the case with our question. Philosophers have been wrestling with it for centuries, and one of the core issues they’ve tackled is what they call the diachronic identity—a fancy term for a simple, yet profound, puzzle: What makes you the same person over time?

My six-year-old self was physically and mentally a world away from the person I am now, yet I have no doubt that he was me. So, what connects us? Broadly, the answers to this puzzle fall into two major camps.

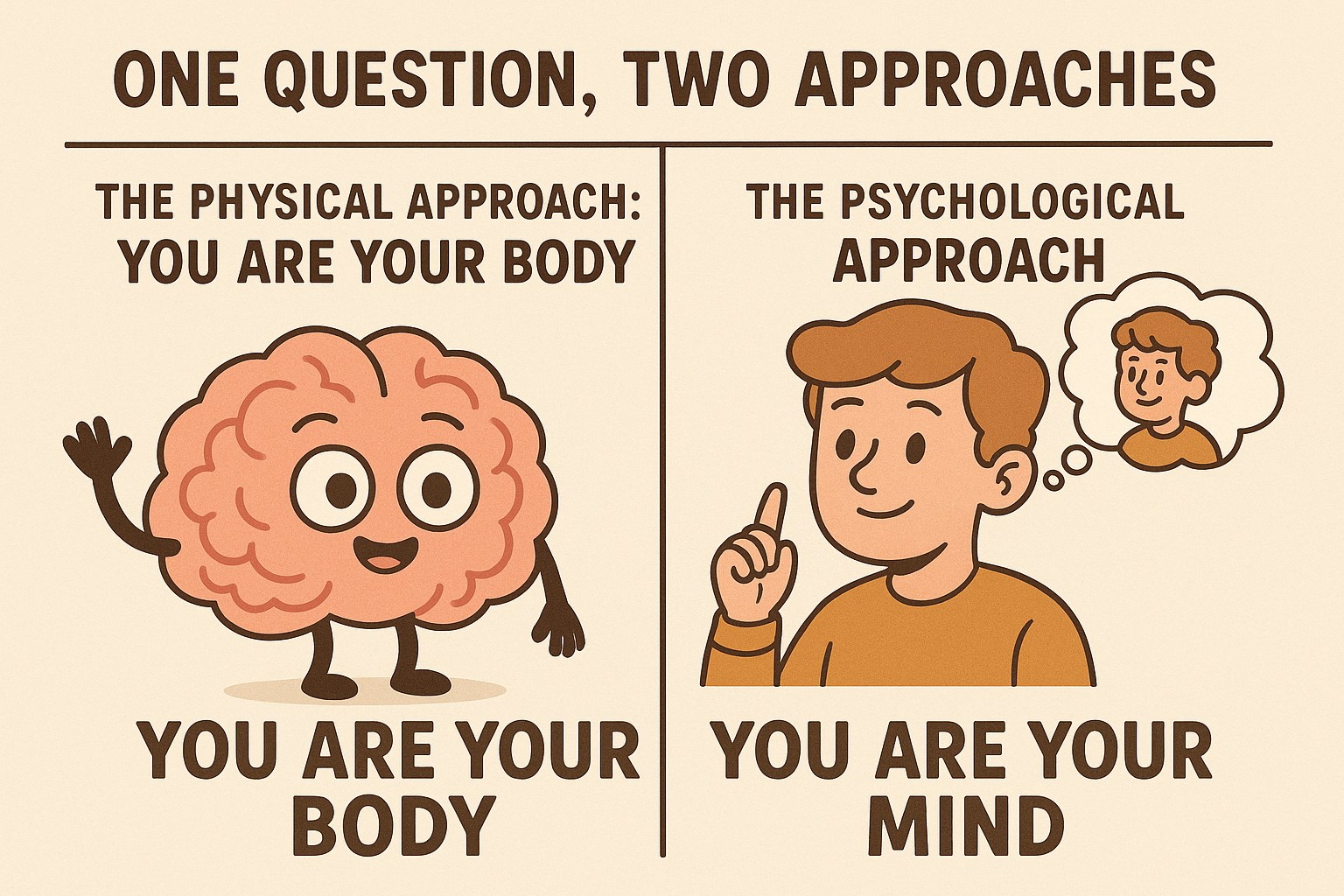

You are your body

The first is the physical approach, sometimes called animalism. It argues that, at your core, you are a biological organism. Your identity is grounded in the continuous, uninterrupted existence of your body, and more specifically, your brain. The logic is intuitive: you could lose an arm and still be you, but if a disease like Alzheimer’s were to erase your mental life, many would argue that the “you” they knew is gone. From this perspective, your identity is tied to the living, functioning organism. Some even take it a step further, suggesting our fundamental self is encoded in our unique DNA, though most philosophers see that as more of a blueprint than the finished building.

You are your mind

On the complete opposite side of the ring is the psychological approach. This view argues that what matters isn’t the continuity of your body, but the continuity of your mental life. It’s not the physical brain that makes you you, but the stream of consciousness it produces. You are the same person you were years ago because you share a conscious link to that person’s experiences through memory.

The classic champion of this idea is the philosopher John Locke. He famously proposed a thought experiment: if the consciousness of a prince were transferred into the body of a cobbler, the resulting person would still be the prince, because they would have the prince’s memories and experiences. For Locke, your mind—that abstract collection of memories and awareness—is more fundamental to your identity than the body it happens to inhabit. This can remind us of one famous law principle, the reason you can be held accountable for an action committed years ago is that we assume a continuous chain of consciousness links you to the person who performed it. In the eyes of the law, you are one and the same.

What psychology says on this

While philosophy wrestles with what makes you the same person over time, psychology offers a brilliant model for how we experience the self in the present moment. William James distinguished between two aspects of the self:

- The “Me” is the self as an object—everything you can observe and describe about yourself. It’s your physical body, your clothes, your home, and your possessions. It’s also how your friends and family perceive you, the different social roles you play.

- The “I” is the self as the subject. It’s the more mysterious part: the pure ego, the thinker, the observer. It’s the part of you that is aware of the “Me.” It’s the “I” that is writing this post, and it’s the “I” in you that is reading it. When you look in the mirror, the “I” is the one doing the seeing.